The advances in technology are mind-boggling. Thirty years ago, the Internet was a mostly text-based medium that researchers used, and cell phones, tablets and smartwatches were science fiction. Today we can hardly survive without them. This technology, however, is paving the way to make elections superfluous through emotional manipulation.

Emotions are an important component of human decision-making, and our election process is no exception. They took a major leap forward in the 1964 US presidential election when the Lyndon Johnson campaign introduced the Daisy Girl advertisement to invoke fear by implying that Barry Goldwater might start a nuclear war. The ad featured a three-year-old girl counting and plucking petals from a daisy juxtaposed with a nuclear explosion.

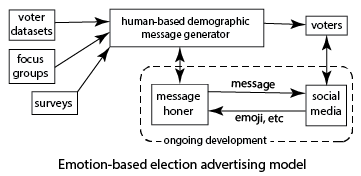

Today emotional manipulation has spawned a $14 billion industry; enough to spend $90 per vote cast in the 2020 national elections. The election industry slices and dices huge voter datasets into demographically distinct audiences for targeted, emotion-based advertising. Surveys and focus groups match specific demographics to specific issues, and a statistical model of persuadability is applied to each voter. Then specific voters are selected for phone, mail or email messages focusing on the issues and arguments that would best persuade them. This current model, shown in the top portion of this figure, has been in use for decades.

Over the past several years a new model has been emerging, shown in the area inside the dotted box. It uses a feedback loop where messages can be tried and improved in hours, as opposed to weeks using the older surveys-and-focus-groups approach. The new model couples the Internet and social media to give feedback through companies like Twitter and Facebook, which allows for the generation of subsequent, more compelling content to influence voters. Ongoing research in the connection between emotions and emoji, hashtags and social media comments is greatly improving the potency of these messages.

The social media feedback loop is merely a hint of what future elections might be like. Three current areas of development bring that future into sharper focus.

Biometric sensors in smartwatches and other wearable technology are already generating user data on heart rate variability, oxygen saturation, respiration, skin temperature and a single-lead electrocardiogram, all of which make important contributions to health monitoring. Headsets that augment virtual reality experiences or help individuals meditate are showing the popularity and marketability of biometric sensors that measure brain waves. Research is taking wearable sensors to new levels, including wearable computer circuits and a 3D printed exoskeleton glove.

The second area is the translation of the data generated by the biometric sensors into emotions. Ongoing research is focused on increasing the accuracy of emotion identification from the aforementioned biometric data as well as adding galvanic skin response and video-generated facial expressions. This research also has important potential applications including monitoring hospital patients, improving driver-assistance systems and product marketing.

Making the connection between the individual and their generated biometric data and associated emotional response is the last area of development. There will be new ways to gather biometric, facial and speech data that is generated from new ways of delivering multi-sensory messages. Think about your biometric data being recorded in response to a specific message on a digital billboard as you drive by. The who, what, when and where needs to be captured, interpreted and placed into the election industry’s dataset that already includes 3,000 data points on each voter. The ever-expanding Internet coupled to new technologies like edge computing and the Internet of things bring it all together.

The future election world

These areas of development paint a picture of a world where the volume of emotional data is growing exponentially, feedback loops are almost instantaneous, and our emotional data is for sale to the highest bidder. And this is all happening at the individual level. Each individual in the dataset could be profiled with a level of susceptibility for emotional shaping gained from a myriad of monitored data: the response to previous advertisements, episodes of road rage or the emotional reactions to favorite songs.

Interest in this capability goes beyond the election industry. Consider a person thinking about the purchase of a new car. He has negotiated a price with the salesperson and has decided to reflect about it before committing. On his way home from the Honda dealership, he is given a carefully choreographed series of experiences. At a stoplight, he sees an ad on an electronic billboard while the atomizer in his cell phone creates the new car smell and his playlist serves up the Beach Boys’ "Little Honda.” Wearable-technology-provided feedback hones subsequent multi-sensory experiences to evoke the desired emotional response. When he arrives home, he reads a message from the salesperson with a last offer of $50 off, which he accepts. The dealership was prepared to offer as much as a $500 discount, but they did not need to based on the emotional feedback they purchased.

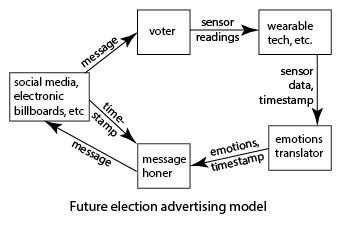

The new election landscape could include instant feedback loops, individualized multisensory messages and emotional profiling. This model shows how it might work with a targeted series of election-based messages.

Starting with the message honer, a multisensory message is sent to one voter through a delivery mechanism like social media. When the ad is delivered to the voter, the date and time is sent back to the message honer and recorded in the dataset. Meanwhile, the voter's smartwatch and smartglasses are recording multiple sensor readings that are sent, along with a timestamp, to the emotions translator. The resulting emotions and timestamp go to the message honer and are recorded in the dataset. The honer also searches for the timestamp that matches the delivery of the advertisement and determines the next message to be sent, then it all starts over again.

We are moving toward a world where enough personally identifiable emotion data is becoming available to profile and subtly shape the thinking of a wide range of voters, which would give control of the outcomes of elections to those who own our data. This election singularity is almost invisible and, on the individual level, easily dismissed with a claim that “I won’t be influenced in this way.”

The answer

By now, you must be asking: won’t Congress address this issue? The short answer: not without a lot of pressure. Emotion-driven campaigns have won many members of Congress their positions, and there is little incentive to change something that has been working for them so effectively. It is the same reason that Congress has failed to solve gerrymandering in over 200 years.

What about groups working on democratic reforms? Arguably the four biggest are ranked choice, term limits, the For the People Act, and the American Academy of Arts and Science’s Our Common Purpose. None of them consider the effect of emotional manipulation on elections, but Strategy 3.4 of Our Common Purpose begins to shine a light on the answer: citizens’ assemblies.

Citizens’ assemblies bring together lottery-selected groups of individuals to solve problems in an environment which eliminates emotional manipulation. They can be used to solve America’s biggest emotion-grabbing issues that are the fodder of election campaigns. Citizens’ assemblies have been used hundreds of times around the world, but the one that best shows how they might help us is the citizens' assembly that solved the abortion issue in the Republic of Ireland.

The Irish citizens assembly on abortion heard from experts and stakeholders, deliberated, and came up with a proposal that passed in a national referendum with 66% in favor. The new law allows abortions in the first few months without cause and abortions for specific reasons in later months. It is a law that originates from the middle ground.

America has strong groups that promote either a pro-life or pro-choice agenda. A recent Gallup poll found that 47% of the American people considered themselves pro-life and 49% pro-choice. Can abortion be solved here in such a polarized environment? What is missing are the nuances; further poll questions found that 48% felt that abortions should be legal only in certain circumstances. A citizen’s assembly can explore the nuances, seek common ground and give voice to a middle-ground proposal.

One of the three biggest components of a citizens’ assembly are the panelists who serve on it. They are selected in a democratic lottery, are anonymous, generally are commissioned to solve one issue, and then are disbanded. Democratic lotteries have a long history; most decision-makers in ancient Greek democracy were chosen by lot.

The second key component is deliberation, where panelists thoughtfully contemplate and devise a decision. First the panelists hear testimony from experts and stakeholders. Then, guided by neutral moderators, they meet in small and large groups to develop and weigh options with an emphasis on logic and reason. Ample time to reflect is built into the process.

How the citizens’ assembly interacts with the outside world is the third key component. The assembly is both recorded and transmitted live in a way that balances transparency, individual privacy and panelist independence from influence. A report is produced with outcomes and related vote tallies, and may include minority reports as well. Depending on the charge of the citizens’ assembly, the report could be immediately enacted into law, referred to a legislative body for consideration or submitted to the voters in the form of a referendum.

Citizens' assembles have successfully tackled contentious and seemingly unsolvable issues such as climate change in Washington state, COVID-19 in Michigan, and numerous ballot initiatives in Oregon and other states. The Republic of Ireland used citizens' assemblies to address other issues, including climate change, marriage equality and aging population challenges.

We can end the threat of election singularity by removing significant emotional issues from political campaigns. And we would also be solving major issues facing our country, like abortion, guns, critical race theory and immigration. The exploitation of emotions must be stopped so that our American democracy can continue.

How can you help? Tell other people about this problem, ask your Member of Congress to support citizens’ assemblies and learn more here.

About the author: Owen Shaffer, Ph.D. is executive director of Democracy Without Elections, a 501(c)3 organization that promotes citizens' assemblies and democratic lotteries, and emeritus professor of computer science at Lander University.